On the morning of the fifth and final day of the Jaipur Literature Festival, I ran into one of its co-directors, William Dalrymple, somewhere on the festival grounds. He asked me how I was holding up.

“It’s a good thing it doesn’t go for six days,” I said. “If it did, we’d all be dead.”

William, a whirling dervish at the best of times, and a veritable hurricane during the festival, agreed. Even he was looking a little peaked.

We were several parties down by this point and had only one lavish shindig to go. On the second night, Charlotte Wood and James Bradley had smuggled me into the HarperCollins party at the City Palace, with its open bar, endless canapes, and thousand candles flickering in the courtyard.

At the behest of a Dutch diplomat down from Delhi, James and I had attended an affair at the Amrapali Museum the following evening, where I got into a slightly heated discussion about Homage to Catalonia with Anna Funder. We had all of us traipsed up to the Amber Fort on the evening of the fourth night, where we lounged about on pillows eating curry and listening to Indian classical music, and now only the Writers’ Ball, an hour out of town at yet another Rajasthani palace, remained.

Tina Brown once described the Jaipur Literature Festival as the greatest literary show on earth. The former editor of Tatler and Vanity Fair, who this year appeared spruiking her book about the British Royals and later sat in front of me during a session in which Pankaj Mishra spoke eloquently on the subject of colonialism, was in large part talking about the social side of the festival: the publishers’ parties, the intimate gatherings of hundreds, the opulent-to-the-point-of-madness of it all.

Most pieces you will read about the JLF, including this one, cannot help but stress the parties. (I should note that I was a so-called Friend of the Festival, which meant I paid a lot for the privilege of attending the parties, or at least those to which I had actually been invited. At the same time, I have since learned that I can spend as much, if not more, buying tickets for individual sessions at Australian festivals, where I don’t have lunch and dinner provided and am unlikely to have half as much fun in the evenings.) It is not uncommon, in Jaipur of an evening, to run into actor and Obama staffer Kal Penn at the bar, turn around and exchange pleasantries with International Booker Prize winner Geetanjali Shree, share a drink with Lok Sabha member and raconteur Shashi Tharoor, and only then realise you’re standing in the ceremonial seat of the Maharaja of Jaipur next to a table festooned with decorative rose petals. As James put it at the time, and has reiterated since, the whole thing is insane.

But this emphasis on the festival’s evenings tends to overshadow an equally salient fact: the event, which this year turned eighteen, is insane during the days as well. These begin at nine, with an hour of Indian classical music, performed on the festival’s main stage in anticipation of the sessions to follow. The latter begin at ten and go until half past six in the evening, unfolding, in the manner of a sizable music festival, across six stages scattered about the grounds of the Hotel Clarks Amer. The hotel has been hosting the festival since 2022, when crowd sizes forced it out of its original home at the Diggi Palace in the centre of town. This year, according to festival organisers, some three hundred thousand people attended the event, listening to six hundred authors talk in twenty-six languages (thirteen of them Indian) about literature, history, art, food, and everything in between. As William put it in his opening address, which followed those of his co-directors, Sanjoy K Roy and Namita Gokhale, the JLF boasted six Nobel Prize winners, eleven Pulitzer winners, and five Booker winners or shortlistees. This is not your usual writers’ festival.

Having attended the festival previously, I came into this year with something of a plan. I knew in advance that there would be certain speakers I would be able to see elsewhere, at other times, and for the most part I avoided these in favour of sessions that would not be repeated anywhere else. As a result, I sat in on poets like Lakshmi Puri and novelists like Aishwarya Jha. I listened to Hindol Sengupta and Janaki Bakhle discuss the origins of political Hinduism and the nationalism that so commands India today. On my first afternoon, I wandered unknowingly into an eye-opening session on Kalachuvadu, the Nagercoil-based publishing house, which, in addition to championing Tamil writing in India and abroad, has published Tamil-language translations of Dostoevsky, Kadare, Kapuściński, and others. More than two thirds of this year’s festival was dedicated to Indian writing, and it seemed to me a waste of a trip, not to mention of a learning opportunity, to not at least try and engage with at least some of it.

Of course, in other cases, I made exceptions, whether because I’m a Robert Service groupie, was keen to hear William and Anita Anand record their Empire podcast live, or because I wanted to support the Australian contingent, and not only because they had snuck me into a party. While a little cultural cringe is not beneath me, I did feel it to some extent my duty to go and support my fellow antipodeans. Wood spoke about her Booker-shortlisted Stone Yard Devotional, in a session that gradually become a deep dive into how and why we write. James, in town with Deep Water: The World in the Ocean, the non-fiction book he was born to write, spoke in tones at once both awestruck and doom-laden about the deep and our deep impact on it, and Funder, in conversation with Bee Rowlatt and the art historian Katy Hessel, took Orwell to task for his treatment of his wife, both on the page and off it. (“Oh, you’re one of those Orwell men,” she said to me later, which, I maintain, wasn’t an argument.)

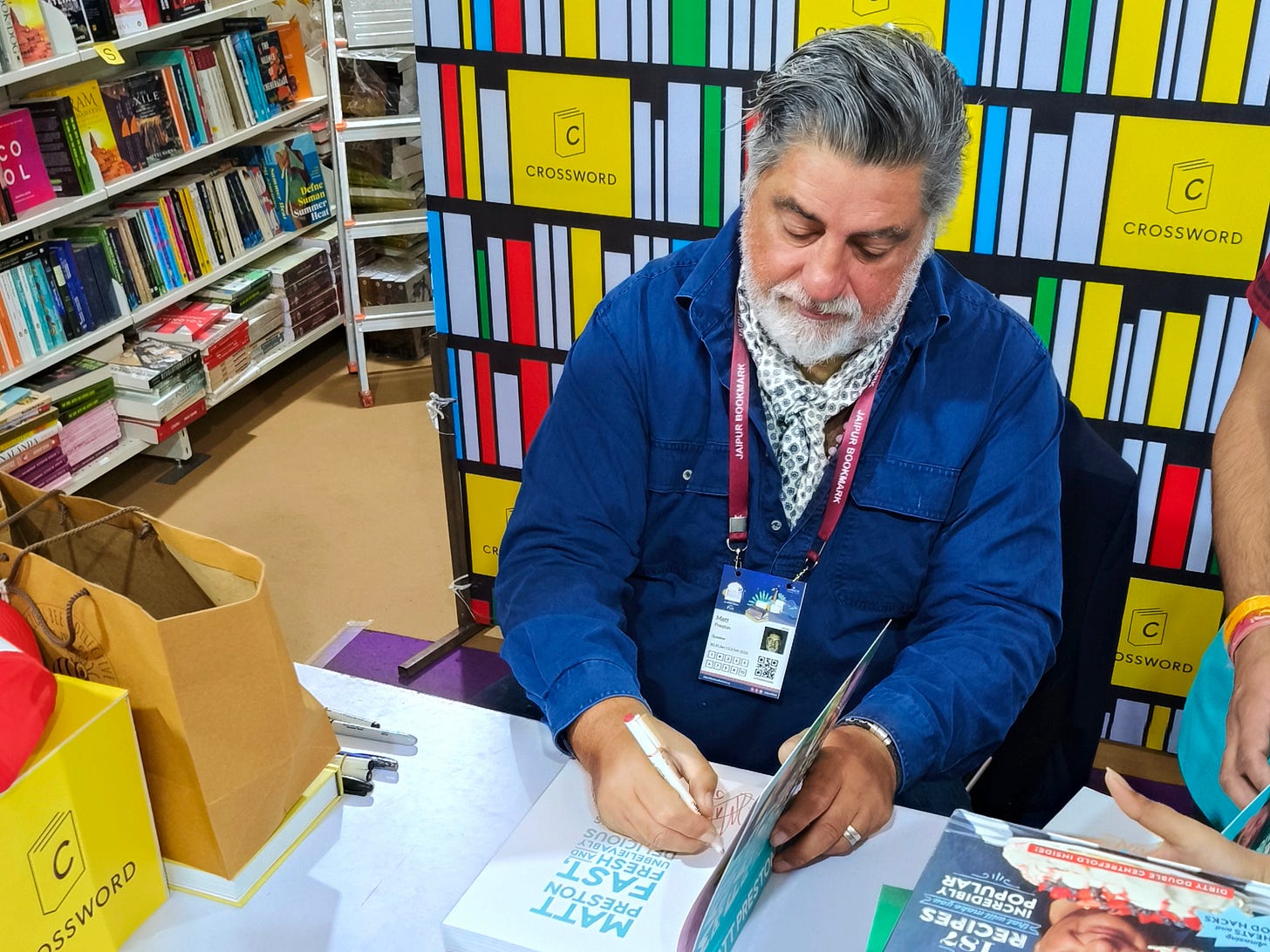

But one Australian loomed large above the others, both literately and figuratively. I had met Matt Preston once or twice in the past, prior to his television career, when he was still a critic, a jobbing hack, writing for the Herald Sun. In Jaipur, he was a bona fide celebrity, in more selfies with fans over the course of five days than any other author in attendance. MasterChef Australia, it seems, is very big in India. (It was telling that, as the week wore on, Preston put away his purple three-piece and cravats and opted instead to dress like an American truck driver, though his aviators and trucker cap did little to disguise his telltale silhouette. I don’t think he was fooling anyone.)

Perhaps because history is William’s bailiwick, and because his rolodex is thus suitably deep, the JLF is nothing if not one of the strongest historians’ festivals in the world. In addition to Service, and William himself, the latter discussing The Golden Road, this year’s edition boasted Jane Ohlmeyer on Ireland as imperial laboratory, Barnaby Rogerson on the origins of the Shia-Sunni divide, and Tim Mackintosh-Smith on the three-thousand-year history of the Arabs. (I met the latter two by chance one afternoon and discussed Norman Lewis with them over chai, which is the sort of thing that just seems to happen in Jaipur.)

But while Middle Eastern history loomed large, the real standing-room-only sessions, for the second year running, were far more concerned with the region’s present. Haaretz correspondent Gideon Levy, lawyer and author Selma Dabbagh, and Pankaj Mishra all spoke passionately and at length about Gaza. It was in these sessions that the JLF’s usually excellent audience Q&As—there is very little more-of-a-statement-type stuff in Jaipur, with people snappy, succinct, and armed with actual questions—gave way a little under the weight of the topic.

One serial questioner, who self-identified as a Zionist (which was a pretty brave thing to do given which way the winds were blowing throughout the audience), accused the JLF of only platforming pro-Palestinian voices. As William responded, Palestinians were actually outnumbered by Israelis at the festival, three to one, and the idea for Mishra’s panel was born when London’s Barbican backed out of hosting a London Review of Books lecture series in which Mishra was to deliver a speech titled ‘The Shoah After Gaza’.

“One of the great glories of this country is that we can speak about these issues here,” William said.

Well, yes, but only to a point. If I were to offer a single criticism of this year’s JLF, it would be that, at no point, in all these Israel-Palestine sessions, were the parallels with Kashmir mentioned, nor India’s status as the single largest buyer, not only of Israeli conventional weapons, but also of a range of Israeli surveillance technology and security expertise. This is in striking contrast to last year, when Antony Loewenstein floored his audience—you could honestly have heard a pin drop—by daring to make these facts plain.

The Writers’ Ball was an affair to remember, which is why it’s a shame that I don’t remember much of it. Sitting at outdoor tables between the open bar and the bain-maries, James and I had dinner with the Irish contingent, as well as with the Sundaram Climate Institute’s Mridula Ramesh and paleontologist Steve Brusatte. (It turns out that MasterChef Australia is big everywhere. Brusatte, who is American, turned out to be a fan of Preston’s, too.) Before long, and without quite knowing how, I found myself discussing freelance journalism with Sophy Roberts and Georgina and Peter Godwin. We agreed that it was pretty ironic that none of us had read or written a word for the better part of a week.

I may not remember the party too clearly, but I do remember the highlight of my week. As I drove out of the Pink City the next morning, I couldn’t help but reflect on the fact that, less than twenty-four hours earlier, I had been in the audience during the festival’s penultimate session, when the grandson of Mahatma Gandhi and the great-grandson of Leo Tolstoy appeared on stage in conversation. The flame of non-violence resistance, they agreed, may in fact have been fanned, and perhaps even sparked, by the forty-year-old Gandhi’s much older pen pal, who urged him to fight the British with love. Whatever the case, to have seen these two on stage—“I don’t know if Gandhi had read Anna Karenina,” Gopalkrishna Gandhi said at one point, “but if he did not, it was Gandhi’s loss”—seemed to me a once-in-a-lifetime, only-in-Jaipur kind of experience. It, too, like the rest of it, was insane. I took out a book and opened it to the first page.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Weariness Makes a Good Mattress to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.