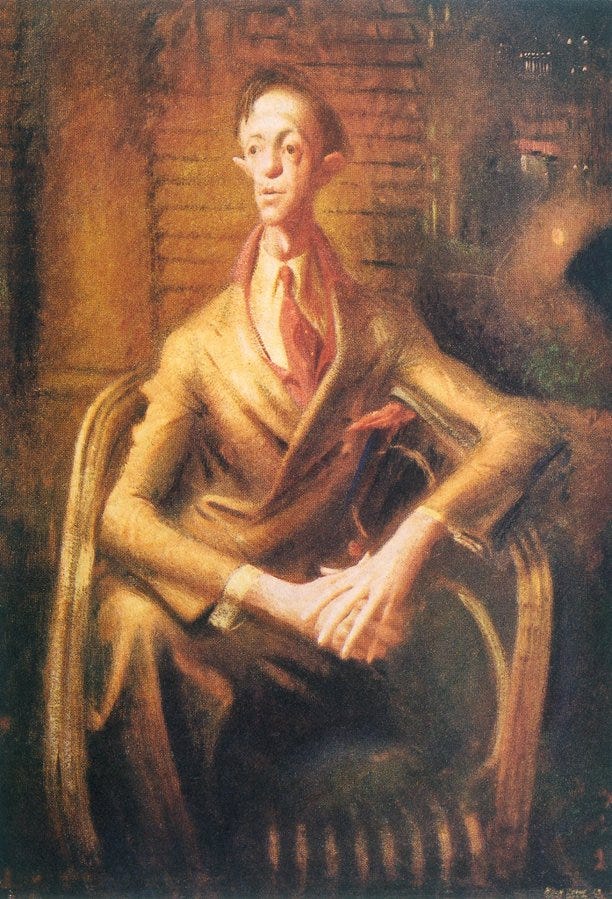

Eagle-eyed readers will have noticed that the avatar for this Substack is a detail from William Dobell’s 1935 painting, ‘Young man sleeping’. I am no great fan of Dobell, whose work I mostly consider a ghoulish facsimile of George Washington Lambert’s. But if you’re going to call your Substack ‘Weariness Makes a Good Mattress’—a line stolen from Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Paramo, as even-more-eagle-eyed readers will have noticed—you may as well illustrate it correctly.

(It also helps that the painting looks like the vast majority of my twenties and a not inconsiderable chunk of my thirties.)

What I like most about Dobell is the fact that he got sued for winning the 1943 Archibald Prize, on the grounds that his portrait of the artist Joshua Smith was considered by some of the people he beat to be a “caricature” rather than a “portrait”. The claim was dismissed, primarily because it was, as I think you will agree, silly. (It did upset Dobell a lot, though, and he moved into landscape painting thereafter.) But it’s relevant to what is to follow. The insane level of fear in parts of the Australian art establishment, towards anything even remotely “modern,” was for too long very real. It was the same in literature, architecture, film, and other media. It was also stupid, and we have suffered for it. (For one thing, our international collections tend to suck.)

It started during lockdown, the way so much did back then. It wasn’t about keeping myself sane or anything. It wasn’t even meant to be a project. I was simply tired of Twitter’s tone and my own contribution to it. Melbourne and Sydney, always at one another’s necks, were now seemingly going for one another’s jugulars. There was a lot of nastiness about. I resolved not to tweet anything negative for a month. I decided to be positive.

And so it was that, one morning, I tweeted a picture of Russel Drysdale’s 1948 painting, ‘The cricketers’. I tweeted a different piece of Australian art every day for the next two years.

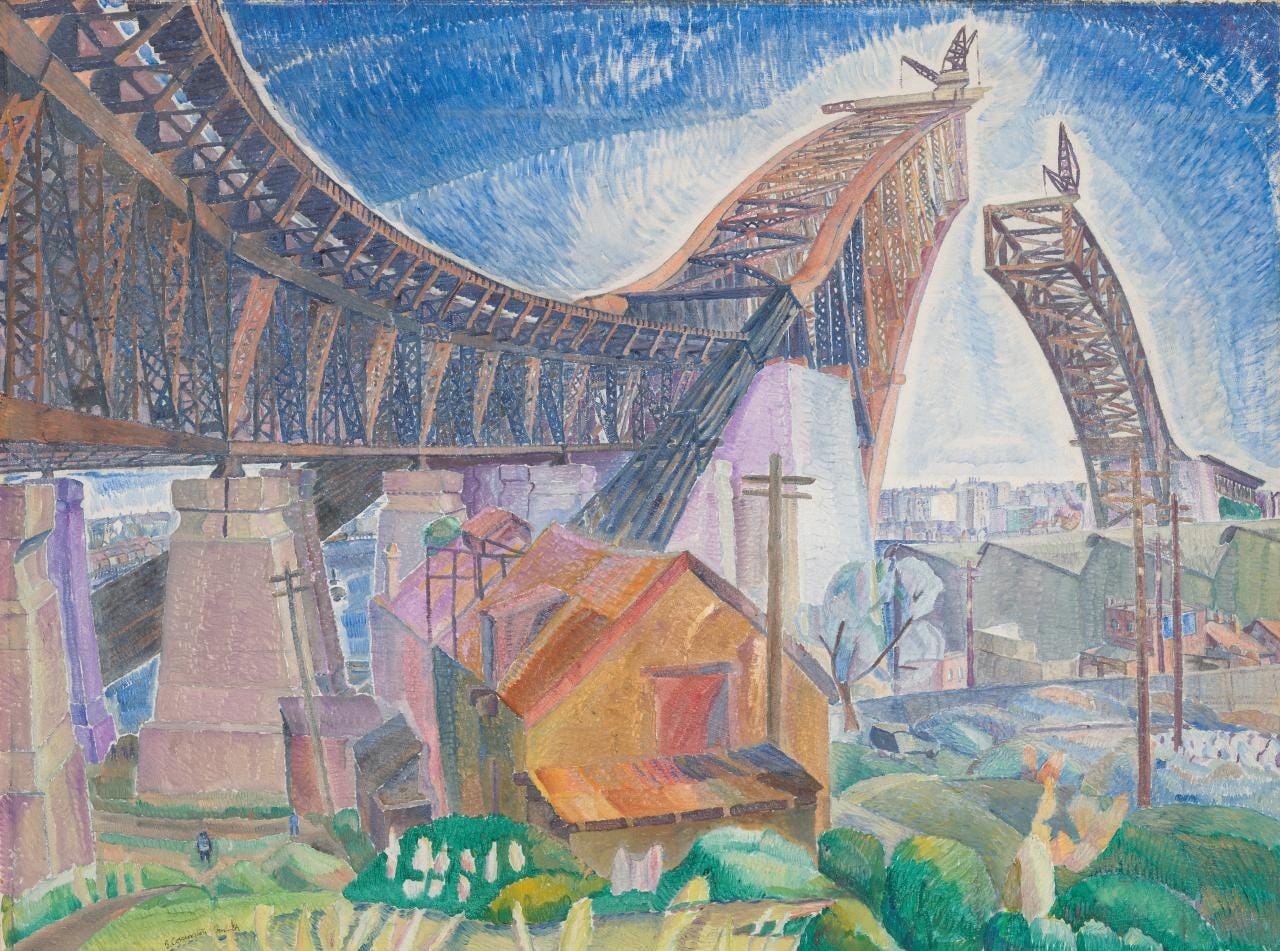

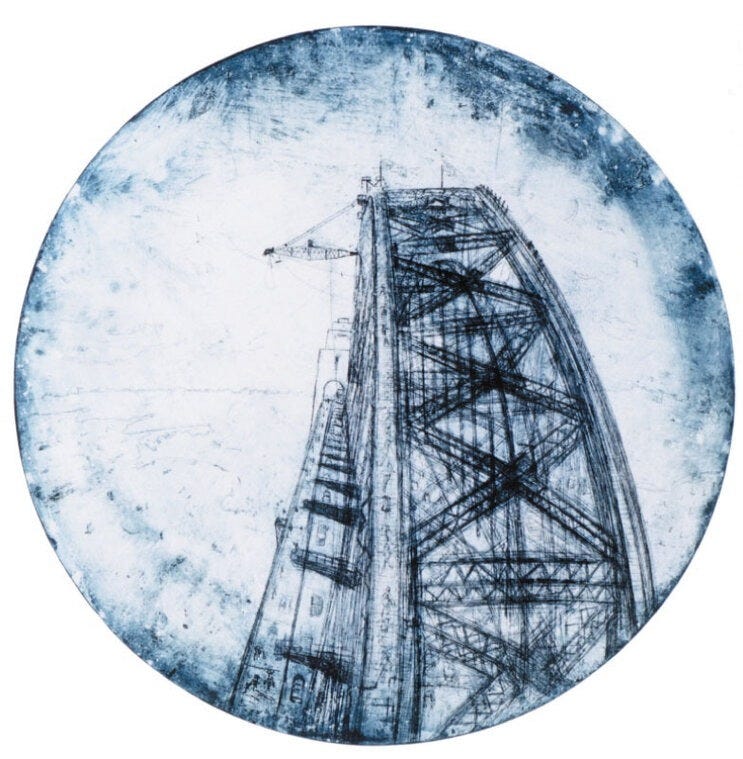

That first one didn’t go viral by any means, but it was popular enough, and popular in an unusual way. Unlike a lot of things on Twitter, and certainly anything I had tweeted before, engagement appeared to be rooted in good feelings rather than in bad. (I wonder, in retrospect, if this didn’t have something to do with the fact that I explained how, when I was growing up, we had a reproduction of ‘The cricketers’ in our hallway. My family still owns that print, or whatever it is, and my parents are bringing it up to me for my birthday.) I decided to try again the next morning, this time with Grace Cossington-Smith’s incredible ‘The Bridge in-curve’. This one did even better.

The next day I did Albert Tucker’s ‘The metamorphosis of Ned Kelly’ and then we were off to the races. I’m not sure when I decided that I was going to aim for fifty-fifty gender parity. I was simply following a template set by those first couple of tweets. I certainly can’t tell you at which point I decided to add biographies into the mix. (I could go back and find out, but searching what has since become X, for any of this stuff, is no longer a productive exercise.) But suddenly this was something I was doing. It was something I was doing, in lockdown, for twenty minutes before work began.

I’m not going to lie. I was chasing engagement. What’s funny is that I didn’t stop once that started to drop off. What’s funny, too, is to go back to these early tweets and look at which paintings I was choosing for each artist. I hadn’t yet decided not to repeat anyone—I hadn’t yet learned that I wouldn’t have to—so it’s amusing to me to think that, rather than one of his Ned Kelly paintings, I went with one of Sidney Nolan’s haunting Antarctica pictures.

Amusing, but perhaps not a bad thing. In any case, it became a characteristic one. I claim no great expertise when it comes to Australian art. I own Robert Hughes’ The Art of Australia and Bernard Smith’s Australian Painting, and I occasionally dipped into both for inspiration. But they were published a very long time ago, mostly focused on the big names, and were very much out-of-date and thus ignorant of anything that happened after about 1970. If I were going to stick to my own self-imposed rules, I was going to have to expand my horizons and learn a few things. Here’s what I walked away with.

1. Australian artists are wildly inventive—just usually a few years late

Almost every major art movement, from the 1890s through to about the mid-1970s, made it to Australia only as it was beginning to wind down elsewhere.

The fact that they made it here at all is testament to the Australian artists who, rather than staying on in Europe or the United States, where they saw what was happening and jumped on the bandwagon, chose, eventually, to come home. (Not all of them did. Bessie Davidson stayed on in Europe and wound up fighting with the French Resistance. Constance Jenkins established an art school in San Francisco that later merged with the California School of Fine Arts. Others, like Nolan, came back and left again.)

This does mean that there was little that originated here (beyond the obvious and notable exception of Indigenous art, which I discuss below). But, as it turns out, that didn’t really matter. Because introducing things like Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, and Surrealism to Australia often gave those movements a bit of last-minute energy, and caused them to develop local characteristics. Indeed, it was often as though a foreign species had been introduced, loosed into the Antipodean strangeness, and the movements evolved in equally strange ways, independently, once they got here. (They were also very often not welcome.)

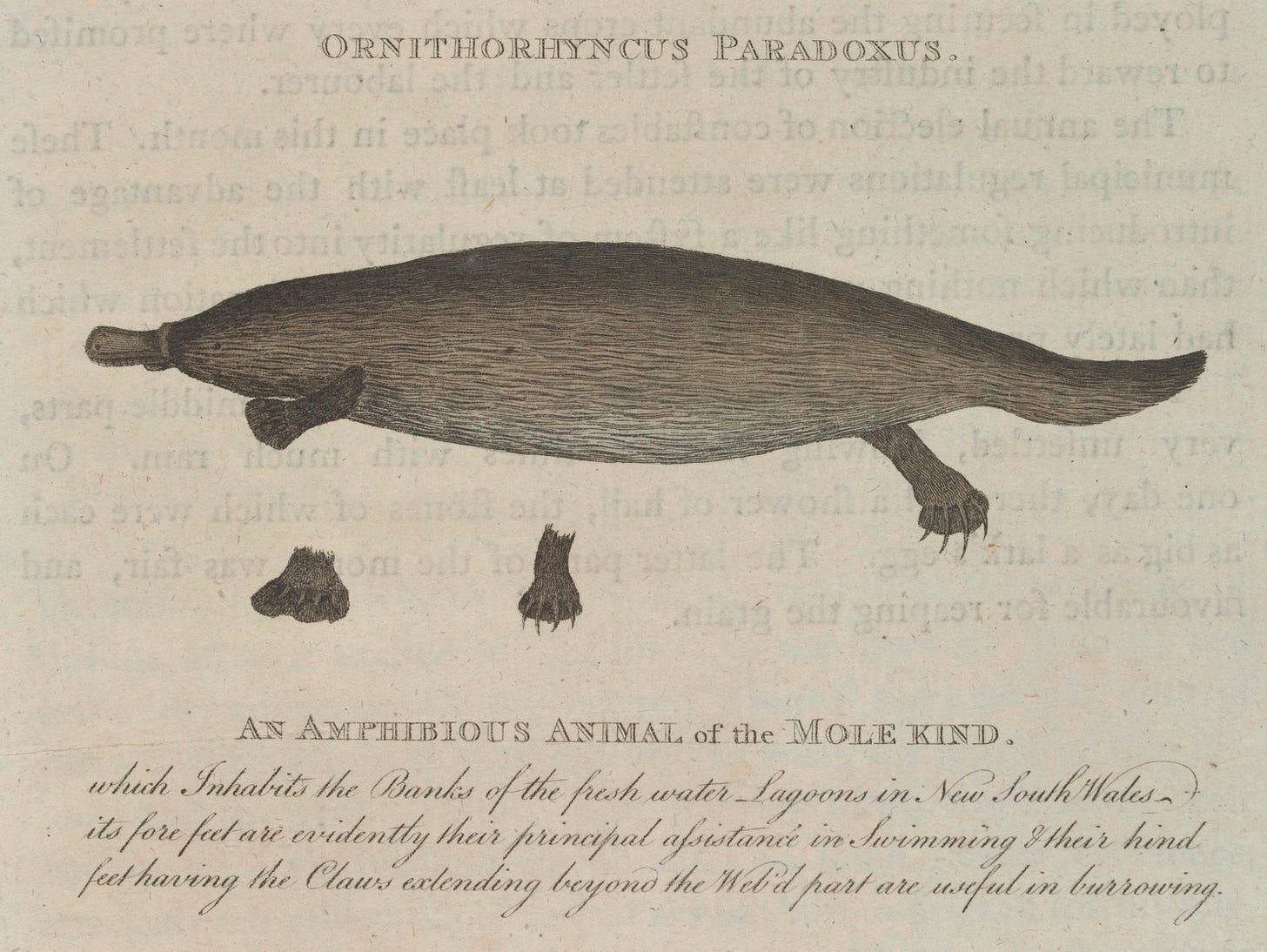

This is not quite the same as the development of the platypus, which evolved here in isolation once the Australian continent broke off from the others, allowing for such oddities as egg-laying mammals. I have toyed, and am toying, with the idea of writing my own little potted history of Australian painting (particularly Australian modernism), the title of which would be Platypus. Anyway, here's the first-known European representation of the animal.

The 1797 sketch of an “Amphibious Animal of the Mole Kind” was sent to the Literary and Philosophical Society in Newcastle-upon-Tyne the following year, by Captain John Hunter, the second Governor of New South Wales. Along with a pelt specimen, the sketch became the basis for George Shaw’s 1799 depiction, the first that was ever published. What the latter image reminds me of is Dürer’s ‘Rhinoceros’, but that’s another story altogether. What is important here is that even Shaw thought he was having his leg pulled. “It naturally excites the idea of some deceptive preparation by artificial means,” he wrote of the pelt. But no. This weird, inexplicable creature—“Ornithorhyncus Paradoxus,” as Hunter had called it—had evolved here, as would Australia’s own strange art.

2. We should remember more women artists than we do—and men are usually the reason we don’t

Consider, if you will, Jessie Scarvell, Hilda Rix Nicholas, and Evelyn Chapman. I could name more, but let’s take these three. Each was a phenomenal painter, especially Nicholas, who was one of the first Australians of any gender to dabble around with Post-Impressionism. All three either quit painting after they got married, or else found it very difficult to keep painting once they did so. I have many problems with Anna Funder’s Wifedom—problems that you are going to hear about at great length very soon—but this part of her argument is correct: marriage too often forces women to become unpaid labourers and sex workers, at the expense of their own desires and goals. Scarvell, a painter of beautiful, Turneresque landscapes, such as 1894’s ‘The lonely margin of the sea’, got hitched and was effectively never heard from again. This, to me, is insane.

This is to say nothing of those, like Jane Sutherland, who never married but nonetheless came up against the brick wall that was the mostly-male world of critics, curators, gallerists, and, it must be said, fellow artists, who tended to decide what was what. Sutherland and her friend, the wonderful Clara Southern, were both shut out entirely from the 1889 9 by 5 Impression exhibition, despite both making work for it. (I’ll leave my argument that “Australian Impressionism” wasn’t Impressionism for another day.) The situation didn’t quickly improve after that. Only three women were exhibited in the NGV’s seminal 1968 contemporary art show, ‘The Field’, which is to me a shocking thing, a whole big bag of mixed nuts.

3. So is our obsession with oil paint

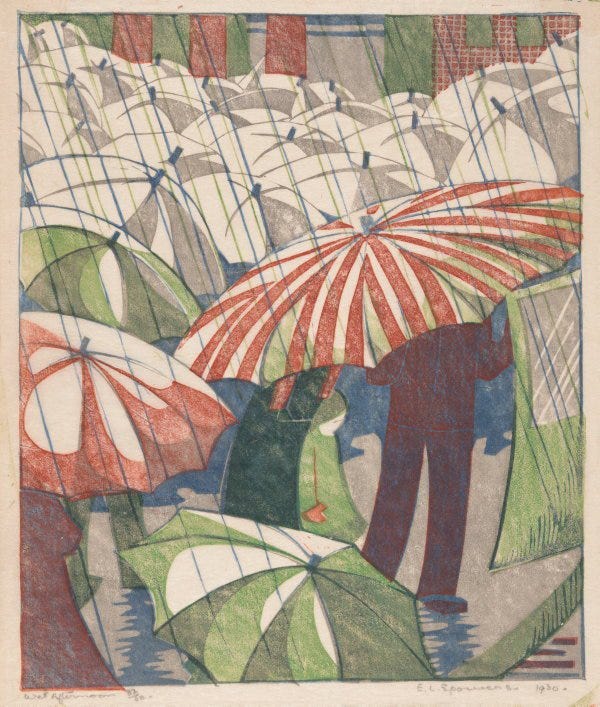

Had my scope been global, I may never have tweeted a painting at all. My great love, as far as the visual arts go, is printmaking, the perfect combination of everything the others have going for them: drawing’s emphasis on line, sculpture’s physicality and reliance on the bicep, painting’s attention to wash and its application, photography’s mechanical reproducibility. (I once interviewed Marco Luccio, a Melbourne-based printmaker, who referred to a print as “the history of the mark”. I think I like this about as much as as I like anything that anyone has ever said about art. I actually think it’s the definition of it.) Australian printmaking has an often-forgotten, often-underground history, ebbing and flowing in popularity and importance. It exploded at RMIT in the 1950s, but, as usual, that was primarily because male artists had turned a hand to it.

But almost all of our best printmakers—Ethel Spowers, Violet Teague, Jessie Traill, the almost too-good Cressida Campbell—are women, not least because women tend to be the people who make the most prints. There are multiple reasons for this, but at least one of them is the fact that printmaking has always existed on a rather interesting line between fine and commercial art—consider, for example, Florence Broadhurst, who was famously murdered in 1977 for no good reason—and, for that matter, between commercial and practical art. (It also has something in common with “craft,” a word often used in the pejorative.) Bookplates, insets, illustrations for the lady’s journals. These were things that women made, and well. Artists like Spowers and Campbell, in particular, make the prints made by our more famous male artists look primitive.

And that’s just the prints. Consider the watercolours of Conrad Martens and the ceramics of Sandra Taylor or Rod Bamford, the latter two of whom I had to research for hours just to cobble together two-hundred and forty characters for their bios. Two of those names are male, but I think you get the general vibe.

Things have changed a good deal, with artists like the sculptor Patricia Piccinini and the tapestry artist Kay Lawrence now held in state and national collections. But it has been hard enough for me to find women who were painting en plein air with the so-called Impressionists at Heidelberg. Imagine the women whose work we never knew existed, because it was crocheted and hung, forgotten, above the hearth.

4. Indigenous art means a lot more than dot painting

I always ummed and ahed a bit about including very much dot painting in my tweets. There were a hundred reasons not do so, not least the history of white people’s exploitation of it. I also don’t know what examples of it are good: these are texts that I can’t, and perhaps shouldn’t or at least needn’t be able, to read. I know what I like, but I often don’t know what it says. I did learn how artists like Albert Namatjira found ways to sneak First Nations knowledge into otherwise staid Western forms, but I also learned that there’s way more to what Indigenous communities produce than dot paintings, especially today. Some of the most exciting contemporary work is being made by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Indeed, in my opinion, it’s the most exciting work, and not for reasons that have anything to do with wokeness. It’s just really good.

Don’t get me wrong. I included some of the great dot painters in my tweets. But the stuff that excites me more is stuff like Zaachariaha Fielding’s Wynne-winning ‘Inma’. It’s so inherently interesting in and of itself, technically accomplished and aesthetically vibrant. These may be my Western standards talking—well, not may be, are—but I make no claim to be able to judge the work otherwise, and in any case these are the standards by which the artists have, at least nominally, chosen or been forced by the art world to be judged. Whatever the case, doesn’t it just sing? The colours of Namatjira? The Olsen-like cosmological richness of Fielding? Everything Tracey Moffatt has ever done? Take away the message, perceived or legit, and tell me you are not enraptured by this stuff.

5. Aesthetic pleasure still matters

Most of the video stuff doesn’t do it for me. The installation stuff falls consistently flat. These are dead ends, much like freelance foreign correspondence was for me. I included bits and pieces from these schools in the tweets because sometimes I needed to. Sometimes, I wanted to name-check someone obvious, and sometimes, especially towards the end, I was out of options and liked the artists’ stories if not their art. (I’m not going to name any of them, but Shaun Gladwell is a person who exists.)

The most popular pieces I tweeted were always, at the very least, things that looked interesting. They didn’t have to be pretty. They could in fact be as ugly as sin. (Adam Cullen lived and died in a state of manic grotesquerie—he shot his own biographer, who happens to be one of my former editors, in the leg—but he could paint that ugliness, and the ugliness was the point.) It didn’t even matter if the bio was fascinating: if the work didn’t hold some essential visual appeal—to be fair on the video artists, I only ever shared stills from their work, and, to be fair on the installation ones, you do kind of have to be there—the piece was not going to do well on the interwebs.

I would actually go a little further than this, because I am someone who likes to get up close to a painting. I like thick, sandy, nasty impasto, paint slathered on to the point that it could poke an eye out. I like to see the brushstrokes and the last faint hints of canvas beneath them. You don’t get this in a Twitter-compressed JPEG, and you certainly can’t zoom in to try. If you believe that subject matter drives engagement on the internet, I have to correct you. It’s the vibe. It’s composition. An ugly, violent, balanced painting will outdo a politically correct but slightly wonky one every time.

Aesthetics matter. We pretend they don’t, especially today. But as Garth Greenwell has written about literature, and Alice Gribben about, well, art, what hits hardest is still what hits us aesthetically, and the absence of political commentary in my art tweets, even when the artist, like Noel Counihan, was a Communist, probably goes some way towards explaining why people liked them.

6. I’m not the only person who doesn't know enough about Australian art

In June 2023, I went to New York, and to MoMA. I had the same experience I have there every time: one of wonder. The pleasure of seeing Picasso’s 1907 ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ and Jasper Johns’ 1954-55 version of ‘Flag’ is undeniable, especially in the flesh. I wonder why that doesn’t happen so much here. I don’t think it’s a quality thing. I think it’s me knowing Picasso and Johns and Van Gogh and Whistler and Matisse and Turner and Rodin and Goya better than I know (or knew) John Perceval or Joy Hester. But shouldn’t I, as an Australian who goes to art galleries, also have those glorious moments of frisson with more than Streeton’s ‘Fire’s on! Templestowe tunnel’ (my favourite Australian painting of the 1800s) and John Olsen’s 1965 ‘Sydney sun’ (my favourite Australian painting of the 1900s)? This is not a shot at the galleries or their curators: one only has so much wall to work with. But my understanding of Australian art exploded because of one accidental tweet. It did so for others, too. Jon Kudelka, one of Australia’s great political cartoonists (and, as an aside, one of its most exceptional printmakers, whose work I collect), told me around the time I was thinking of giving the art tweets up that they had introduced him to some great artists. Yeah, well, me, too.

This isn’t cultural cringe, neither in the original sense of the term, nor in the sense that it has improperly come to be understood. It’s just about access. The national and state collections do their level best to hang what they can then digitise the rest. But it’s a rare loon who spends his time strolling those latter, online halls, even from the comfort of his home during lockdown. Reader, I was that loon. It was worth it.

I ended the tweets on their second anniversary for two simple reasons: it had become too hard—to find the time, to adhere to my rules, to dig up bios for long-forgotten artists who should, I think, have been of note—and because Twitter had changed and I no longer especially wanted to spend my time there. But you have doubtless read a version that particular article, and I am much too tired to rewrite it. If you’ve been on what is now X since it became that, you know the ways in which it has devolved under the leadership of Salvador Dalí. (This is a joke about self-promoting fascists, by the way. At least Dalí could paint.)

When I announced that I was done, I was pleased by the response: some people said it was the main reason they still used the site at all. I have no sense at all that my art tweets will survive there. They might disappear tomorrow. But, for the moment, they remain an impressive archive of what Australian artists, unbeknownst to most of us, have achieved. Search the site for “mclayfield ‘Good morning’.” There are nearly eight hundred Australians there for you to discover.

Or, you know, visit a gallery. The platypus is waiting for you.