Audience swallows tripe

Perhaps Trent Dalton is our Ethel M. Dell?

Earlier this year, when the Sydney Writer’s Festival program was released, I made my usual complaint about the exorbitant price of the tickets. It isn’t worth paying that much, I argued—upwards of forty dollars for some sessions—when the festival is basically an overlong Radio National segment.

That isn’t an exaggeration. The vast majority of SWF moderators are ABC-affiliated or -adjacent, from David Marr and Annabel Crabb to Waleed Aly and The Bookshelf’s Kate Evans, and a not insignificant number of the sessions are recorded for later broadcast on RN. (I paid more than thirty dollars to watch Aly and Scott Stephens interview Anna Funder for The Minefield, mainly in the hope that one or either of them would call her up on her questionable journalistic ethics, which, naturally, they didn’t.)

I don’t blame the festival too much. It knows who’s keeping the lights on. A Venn diagram of RN listeners and SWF ticket holders—of RN listeners and people who live in Paddington, attend STC matinees, have lunch upstairs at the Museum of Contemporary Art, think the Festival of Dangerous Ideas is edgy, erroneously claim to have always voted Labor—is essentially a single circle. These are the sort of people who will buy a thirteen-dollar croissant at the Carriageworks farmers’ market then head over to the festival to drop even more on talks that, in a couple of weeks, they could hear on the radio for free. (In addition to the sessions that are destined for broadcast, the SWF also winds up releasing great swathes on its podcast. Aside from not costing anything, this level of engagement is a lot more convenient than getting up early on a Sunday morning to brave the cold and cavernous prison that is Carriageworks in order to watch someone field a Zoom call from abroad.) The result is that the festival program—far more than those of the smaller neighbourhood-based festivals, such as the Addi Road Writers’ Festival in Marrickville—tends to be a genteel affair tailored specifically to the tastes of an RN listenership.

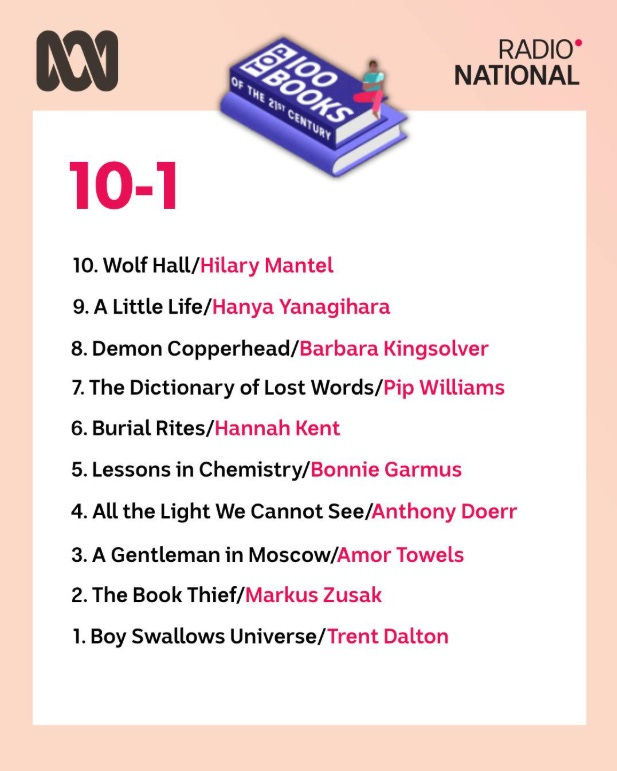

The problem is that, under no circumstances whatsoever, should such people and their tastes be allowed to dictate the programming of a literary festival. They are middlebrow, parochial lovers of the mediocre, connoisseurs of the unchallenging and bland. Their favourite kind of literature is YA that doesn’t call itself that. Don’t believe me? They proved as much over the weekend. After nearly two months of audience polling—287,990 votes were cast in the end, a whopping three quarters of them by women—RN announced its Top 100 Books of the 21st Century. While there were certainly some very good books on the list, albeit further down it than they should have been, the top ten was for the most part an embarrassment:

There are a couple of things that jump out at you here. The first is recency bias, with only The Book Thief and Wolf Hall predating 2010. (Recency bias explains a lot about the list, such as the presence of Charlotte Woods’ Stone Yard Devotional but not her Stella-winning The Natural Way of Things. I can’t imagine there’s any other explanation for why Zadie Smith’s White Teeth—number thirty-one on the New York Times’ recent version of this stunt—didn’t make the cut at all, while Funder’s Wifedom, which is not a good book, appeared at number seventeen. It’s amusing to me that the year with the most books on the list was 2023, which suggests that a lot of people simply voted for the last book they could remember reading.) The second thing that jumps out at you is the fact that more than half of the books in the top ten have been adapted for the screen. It would be interesting to know how many people caught the adaptations on Netflix or Apple before actually, if ever, reading the books, and to know as well how difficult or otherwise the screenwriters found the task of adaptation. The third is that Australia is apparently responsible for four of the top ten books of this century. I know that the poll was an Australian one, but this is obviously ridiculous.

I have never bothered much with Trent Dalton—“the definitive novelist of Scott Morrison’s Australia,” as Catriona Menzies-Pike once damningly called him—on the grounds that I have never been able to get past the first couple of pages of Boy Swallows Universe without gagging on the prose. I suspect that his success comes down, not only to the way he “infantilises his audience by feeding them palatable maxims about history, society and human flourishing,” but also to the fact that he’s mates with half the journalistic establishment and that every publication in the country has labelled him a national treasure. (The Guardian remains a notable exception. Jack Callil on Dalton’s “piping-hot sentimentality” and Beejay Silcox on his “bleakly retrograde” politics are both necessary correctives to the gushing.)

But while it’s true that the Australian media tends to function like a herd of elephants forming an alert circle, I don’t think Dalton’s success can be attributed exclusively to the praise of his colleagues. (It’s not as though anyone actually buys the weekend papers.) It also has something to do with what A. A. Phillips, in his famous essay on the Cultural Cringe, called the “Cringe Inverted”. This is a kind of overcompensating jingoism that has been ascendent in Australia for decades—“Culture with a capital C has lost its erstwhile diffidence,” Clive James wrote in 1976, “but in many instances seems to have replaced it with a bombast equally parochial”—but that found its ultimate and emptiest expression in Morrison’s “How good is Australia?” nonsense. (It’s the same thing that causes the commercial news networks to act as though every Australian nominated for an Oscar is a shoe-in to win until they lose.) Aside from the fact that the best Australian books on the list mostly appear buried somewhere towards the back—and that Australian authors like Michelle de Kretser, Gerald Murnane, and Shirley Hazzard don’t appear on it at all—it seems to me that the full-scale repudiation of the Cringe hasn’t resulted in a celebration of our best work, but rather in an unthinking celebration of our weakest, or at least most middling. (Nick Bryant unwittingly proves the point in his tubthumping ABC piece about the list. He would do well to remember that Phillips warned that the opposite of the Cringe is “not the Strut, but a relaxed erectness of carriage.” I wouldn’t so loudly proclaim this as a watershed moment, mate. We just announced to the entire world that our favourite ice cream flavour is vanilla.)

More than anything, however, I think the list reflects how unwilling Australian readers are to be challenged, either by ideas or by style. It is striking how many people will put down a book that doesn’t immediately flatter or placate them—that doesn’t immediately reward them with the junk high of recognition or reassure them that it’s going to proceed in much the same way as other fictional narratives—and how much bad writing they will willingly endure in the case of one that does.

This is as true of the gatekeepers as it is of the readers. I remember once watching the ABC’s First Tuesday Book Club and being shocked when the panel, which included Marieke Hardy and Leigh Sales, shot down host Jennifer Byrne when she complained that the prose in Ann Tyler’s A Spool of Blue Thread was bad. That, they argued, was not the point. The story was compelling. It was moving. When Byrne argued that you had to be able to read the story without grinding your teeth before you could be moved by it, they doubled down. Not one of them—including Hardy, which is a little concerning given she ran the Melbourne Writers’ Festival for two years—engaged with Byrne’s critique of the writing as writing. The writing didn’t matter.

It’s important to remember that this dismissal of form in favour of feels didn’t take place in your neighbour’s house while everyone was drinking wine and eating cheese. It took place on what was then Australia’s only television show dedicated to books. (There are none now, so complaining about it seems a little bit churlish. I’d rather it than nothing at all.) While there are certainly exceptions to the rule—Claire Nichols’ recent interview with Peter Carey abot The Truly History of the Kelly Gang comes to mind—the RN shows tend to be similarly story- and character-focused to the exclusion of all else. When prose and sentence-making do come up, it’s usually only to note the extent to which a book does or doesn’t conform to a narrow definition of the lyrical. This matters. It’s thanks to these shows, alongside the festivals at which their hosts appear as moderators, that this has become the primary model, and these the primary parameters, for most mainstream literary discourse in Australia. (One recent, rather amusing exception was this year’s SWF ‘State of the Art’ panel, which usually involves two or three of the festival’s big-name guests answering the usual, tired questions about their most recent books. This year, apparently a bit miffed that they weren’t going to get to talk about, well, the state of the art, Rumaan Alam, Robbie Arnott, Samantha Harvey, and Torrey Peters hijacked the session, ignored the questions, and simply started talking to one another. It was easily the most enlightening session of the festival.)

Obviously, there are other places to talk books: universities, journals, Substack, residencies, the penniless down-and-dirty spaces that seemed a lot more numerous in my twenties than they do now (mostly because I’m no longer in my twenties and haven’t any idea where to find them). These are where I prefer to spend my time and energy, but they ultimately have little influence on how the majority of readers think about books, namely because they don’t perpetuate the permission structures that allow people to ignore how the things are actually written.

Substack is awash in pieces about this sort of thing: the point of literature, the point of reading. We have argued and will argue again about whether literature should provide moral instruction, engender empathy, model radical politics, normalise kink. We have argued about sentences, about style for its own sake. The site teems with critiques and defences of “poptimism,” which are relevant to fields of endeavour beyond music, such as the writing of airport novels and the deliberate confusion of these with quality. There have even been a couple of good pieces about why all Australian literature is YA and—suggesting that the Cringe is still very much alive—about its “necessarily parasitic relationship to the metropole and ‘culture’”:

We see it today in criticism that insists on connecting new Aussie books to American forebears; in the dim facsimiles of globally successful genre writing that presses major and minor churn into airport bookstores each financial year; in the constant checking of the exits by writers who don’t ultimately believe that writing is possible.

I know that middlebrow taste isn’t unique to Australia, and that it isn’t anything new. (Whenever I’m feeling down about what other people are reading, which is in any case a ridiculous thing to feel, I always go back to Orwell’s essay about working in a bookstore: “[O]f all the authors in our library the one who ‘went out’ the best was—Priestley? Hemingway? Walpole? Wodehouse? No, Ethel M. Dell, with Warwick Deeping a good second…” Perhaps Trent Dalton is our Ethel M. Dell?) I know, too, that to have a national radio network that’s willing to dedicate an entire weekend to books is, whatever the actual content of the broadcast, a positive thing for which we should be grateful. At the same time, I can’t help but feel that RN’s list, and especially its top ten, says something kind of depressing about what books we value, why we value them, and how we talk about that value. I’m not sure whether it’s a chicken-and-egg scenario or a tail-wagging-dog one. Are reader tastes setting the terms? Are publishing decisions determining tastes? Or are readers, writers, publishers, and journalists all stuck in some ungodly feedback loop in which everyone’s constantly agreeing with one another without ever stopping to ask whether they should? Who and where in the hivemind is the queen?

Well said, Matt. I'm upgrading my subscription to you - this is lucid, and only as polemical as this moment needs it to be, which is too rare not to incentivise.

The Canberra edition (they're run by template, of course) is this weekend. Thankfully, someone got Sheila Fitzpatrick, and Darren Rix is promising. Otherwise, all this is true here too. A depressing fate for the place that once hosted parties with Hopes, Wrights, Campbells, and Steads in attendance.

Also, I've always had a quiet laugh at the "festival of trope" [quotation marks sic]. In An Gaeilg (Irish), a ménage à trois is a "Féile na Sé gCos" or "festival of the six feet".

In general, "féile na" (festival of) is mostly used to take the piss out of exactly this kind of self-congratulaion. With so many self-forgotten Celts in attendance, one wonders if it's a Freudian slip.

This is all before I get going on their very carefully presented obsession with adolescent malehood (see Helen Garner's The Season). A Lacan or a Zizek would have a field day with it all. It's a thrill to know I'm less alone than I thought in noticing the rot.

Fantastic piece, and it didn’t even mention the lack or shocking quality of the non-fiction books that polled (Wifedom notwithstanding).