A wild colonial boy

Adam Lindsay Gordon in Mount Gambier and Port MacDonnell

I recently became a paid subscriber to Sam Dalrymple’s ‘Travels of Samwise’, mostly in order to gain access to some of his pieces on Delhi.

What I appreciate most about Sam’s newsletter, aside from its always interesting insights into the forgotten or esoteric, is its heavy visual element: every piece is extensively illustrated with photographs of what he’s talking about. After I read his piece on Delhi’s hidden Hindu temples, I found myself paying more attention to my own surrounds, even in Port MacDonnell, where I recently spent a month with my parents to make up for the fact that I’m not going to be spending Christmas with them. I found myself going out of my way to visit attractions that, growing up in and around Mount Gambier, were always there, as plain as day, but to which I had never paid much attention.

Dingley Dell is one of these. The former home of Adam Lindsay Gordon, who lived there between 1864 and 1867, the cottage is a fifteen-minute bike ride from my parents’ house on the Port MacDonnell foreshore. Despite this, I had never visited it until late last week.

Gordon was born in Charlton Kings, Gloucestershire, in 1833. He was in every respect a child of Empire. His father had been a Captain in the Bengal cavalry and his mother came from slaveholding money. (Her father, Robert Gordon, had at one time been Governor of Berbice, a formerly Dutch colony captured by the British in 1796, in what is today Guyana.) The couple were first cousins.

Gordon was educated at Cheltenham College and the Royal Worcester Grammar School. In between, he attended the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, where he was a contemporary of Gordon of Khartoum and Gunner Jingo. He was eventually asked to leave the academy on account of his undisciplined behaviour. Having proved himself a bit of a wild child—at one point he is said to have won a steeplechase on a horse he had technically stolen, and he himself later admitted that his “strength and health were broken” in his youth “by dissipation and humbug”—his father packed him off to Australia, where there was an opening in the South Australian Mounted Police. “You won’t care a bit about leaving everyone behind you,” his father is said to have told him, “and precious few will care about your leaving, either.”

These words were echoed in a poem, ‘To My Sister’, which our young remittance man wrote on the voyage out. It is a self-pitying but unrepentant affair:

My parents bid me cross the flood,

My kindred frowned at me;

They say I have belied my blood,

And stained my pedigree.

But I must turn from those who chide,

And laugh at those who frown;

I cannot quench my stubborn pride,

Nor keep my spirits down.

He arrived in Adelaide at the age of twenty, at the tail end of 1853, and was immediately posted to the Southeast—what is now known in the tourist brochures as the Limestone Coast—where he served for two years as mounted trooper in Mount Gambier and Penola. He left the service in 1855 in order to try his hand at colt-breaking. (“I am not aware that he was dissatisfied with the police force,” wrote Mount Gambier’s Police-Inspector, who was disappointed to lose him, “but I imagine he thinks it more lucrative to be a drover.”)

It was during Gordon’s colt-breaking years that he became friendly with Julian Tenison-Woods, the Catholic priest and geologist who later co-founded the Congregation of the Sisters of St Joseph with Mary MacKillop. (MacKillop was canonised fifteen years ago this month, becoming Australia’s first saint.) Tenison-Woods was impressed by Gordon—he marvelled at the young man’s ability to quote the classics—and took to lending him books and encouraging his writing. Gordon also became close with John Riddoch, the Scottish-born pastoralist and politician who founded the Coonawarra wine region, and who would later serve alongside the poet in the South Australian parliament.

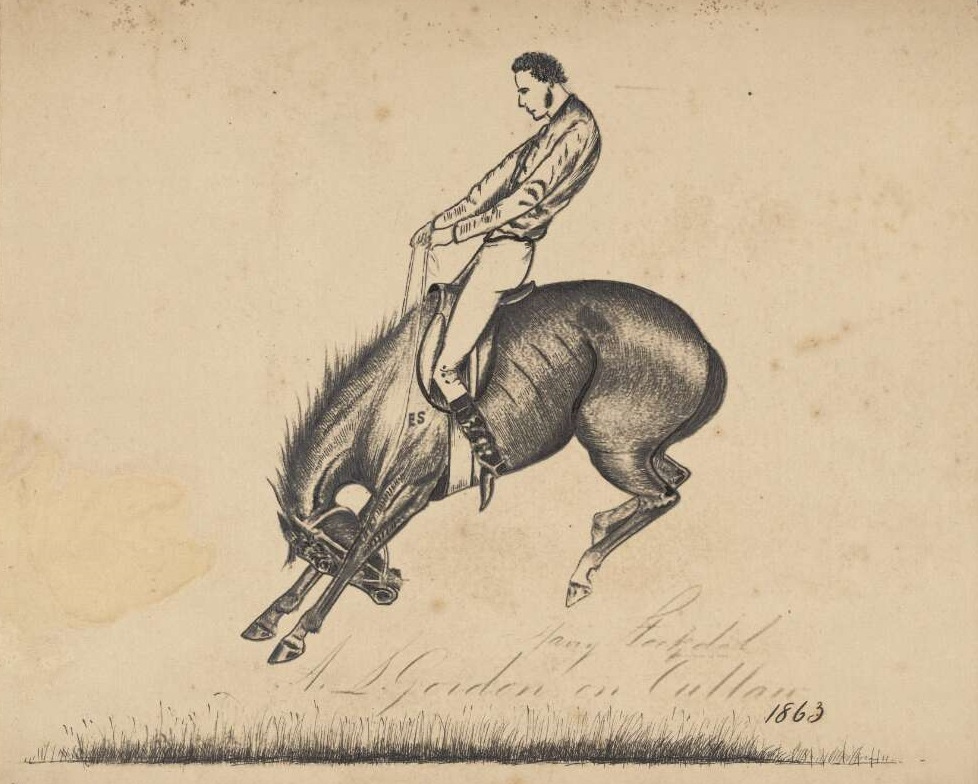

But for the moment—still only a couple of years in the country and as yet unpublished as a poet—it was as a rider of buckjumpers, and as fixture of regional steeplechase meets, that he remained best known in the district he had been forced by circumstance to call home.

In a 2024 article for the Griffith Review, Jeff Sparrow explored “the remarkable literary cult” around Gordon that emerged in the wake of the poet’s death in 1870. The public’s fascination with Gordon lasted into the 1930s, when he was honoured with a bust in Westminster Abbey’s Poet’s Corner, before gradually fading away over the course of the century.

“By 1879,” writes Sparrow, “Marcus Clarke could introduce a collection of Gordon’s work as containing ‘something very like the beginnings of a national school of Australian poetry’.” By the 1970s, however, in the words of critic Brian Elliott, “the writer who, fifty years ago, was regarded as without dispute the most vital and representative of Australian poets, has become for contemporary criticism almost a dead weight”.

“We might consider the reasons for such declining enthusiasm entirely obvious,” writes Sparrow. “When John Howlett Ross titled his 1888 Gordon biography The Laureate of the Centaurs, he, like most critics, took for granted that readers would share Gordon’s equestrian enthusiasms. But in more recent times, even an avowed fan such as Elliott expresses a certain weariness at what he calls the ‘horsey poems’.”

It’s true that you don’t hear much about Gordon’s poetry these days, though you do hear more about it in the Southeast than elsewhere. (I was recently in Penola, where I happened upon an exhibition of previous winners of the Poets of Penola Acquisitive Arts Prize, which requires entries to be explicitly based on the works of Gordon, John Shaw Neilson, or William Henry Ogilvie.) As Sparrow notes at the beginning of his article, as he runs around vox-popping Melbourne businesspeople on their lunch break, Gordon has nothing of the name recognition of later bush poets such as Lawson and Patterson.

But then it’s never been as a poet that Gordon has been most celebrated in Mount Gambier. It isn’t his horsey poems we commemorate so much as the horsey things he did. Mount Gambier’s Border Watch, which was the first outlet to ever publish his work, once ran a timeline of Gordon’s life that included, not only every poem he ever published, but every racing meet he ever attended. Victoria seems more interested in his riding, too. He was posthumously inducted into the Australian Jumps Racing Association’s Gallery of Champions in 2014 and became a Colonial Era Inductee to the Australian Racing Hall of Fame in 2023. There is a plaque at Flemington Racecourse in Melbourne that commemorates the day he won three steeplechases in a single afternoon. But I’d wager that Mount Gambier is the only place that has ever gone so far as to immortalise his acts of mindless daredevilry as well.

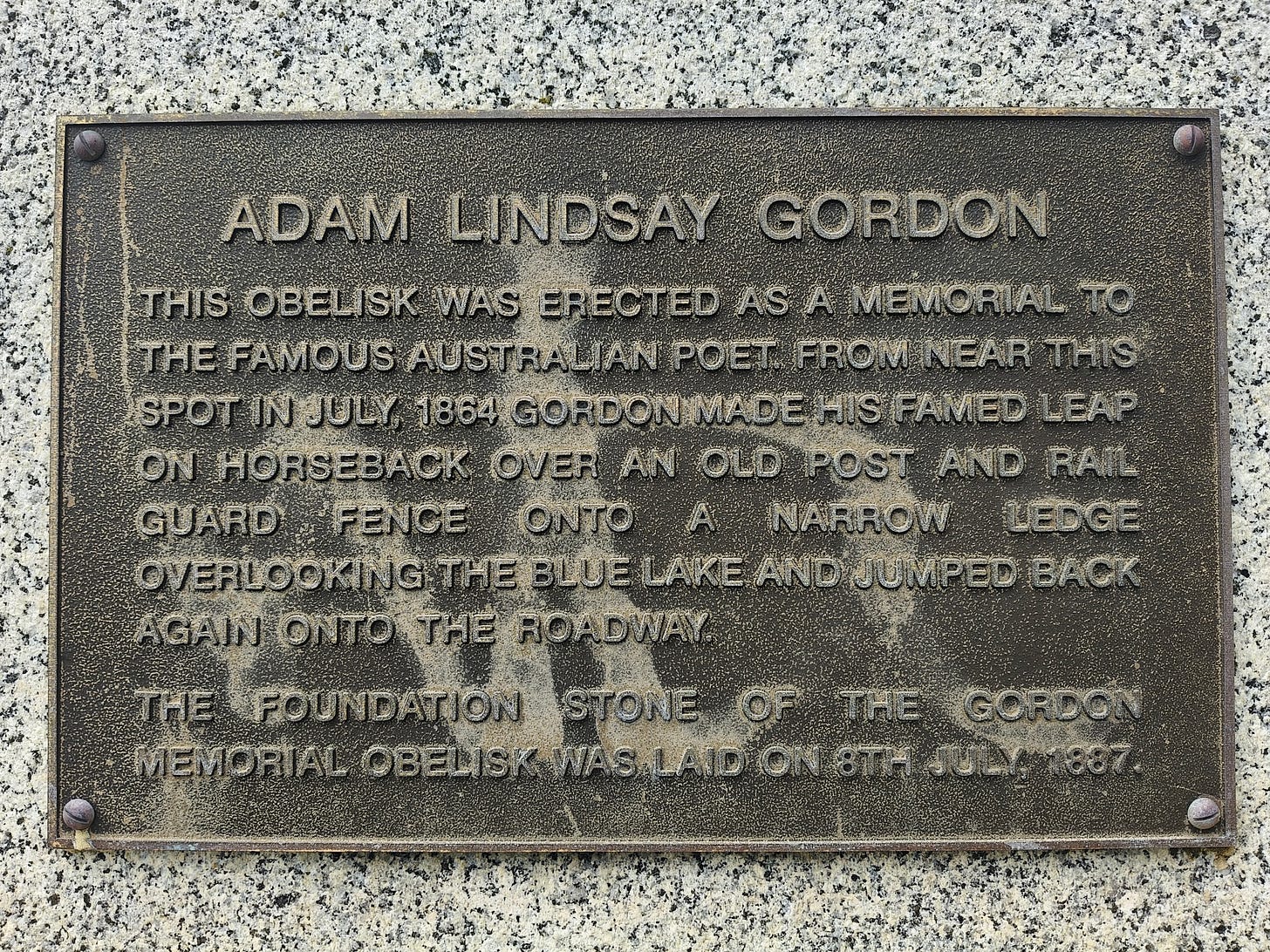

On 28 July 1864, Gordon was riding around the Blue Lake when, during a game of reckless one-upmanship, he jumped his horse, Red Lancer, over a guard fence, landed it on a narrow ledge some sixty metres above the water, and jumped it back again. “There was nothing in the jump [itself],” explained the Sydney Morning Herald more than fifty years later.

[H]undreds of good riders on good horses have jumped three-rail fences. There was everything in this jump [though], because the space for landing and for take-off was so scanty. If horse or rider had made a mistake they had the best chance in the world of going over the almost perpendicular cliff…

In 1887, when Riddoch laid the foundation stone for the obelisk that commemorates the leap today—a piece of solid granite rising from a base of grey and pink dolomite—he correctly noted that “some people may be inclined to question the wisdom of our commemorating the performance of such a feat”. He also made it clear that, as far as the district was concerned, Gordon’s horsemanship was every bit as important as his poetry:

Gordon’s beautiful poems have become known wherever the English language is spoken and his feats on the hunting field and as steeplechase rider will be remembered in Australia for all time. This beautiful monument, of which we have now laid the foundation stone, is within view of the scene of one of the most sensational and wonderful feats of horsemanship ever carried out in Australia, and will keep his memory green, at all events in this town and neighbourhood—a town and neighbourhood he loved so much, and to which, as one of its representatives in Parliament, he gave an honourable service.

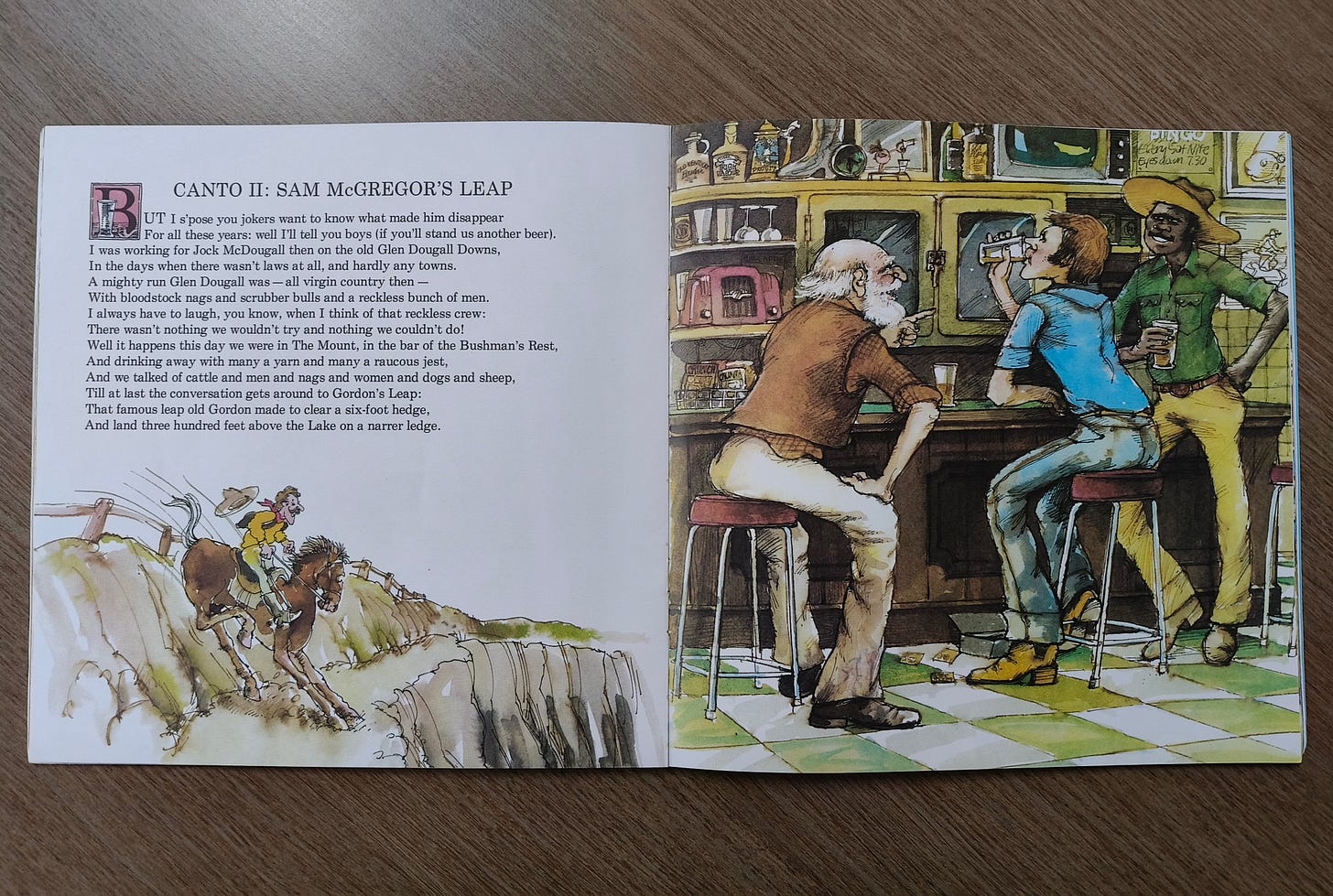

There are lot of inconsistencies in the accounts of Gordon’s leap. According to some, the poet was riding with a group of friends at the conclusion of Mount Gambier’s Border Steeplechase, in which he’d placed third, and others that he was out hunting kangaroos with only one close friend for company. (The friend in question, William Trainor, was more than a little obsessed with Gordon, buying and ultimately occupying the burial plot next to the latter’s grave. If he was the only man present on the day, you’d have to take his claims with a whole shakerful of salt.) The author of an 1897 guide to popular South Australian cycling tours was sceptical that the leap had happened at all. “From a brave jump the account has now assumed proportions sensational even in fiction,” he wrote. It doesn’t help that the monument wasn’t installed until more than twenty years had passed, and that no one knew then, and certainly doesn’t know now, where exactly the leap is supposed to have taken place. I am reminded of Graham Jenkin’s children’s book, The Ballad of the Blue Lake Bunyip, which exposed me to the story as a child. Two stockmen have ridden into Mount Gambier and an old-timer is bending their ears over a beer:

And we talked of cattle and men and nags and women and dogs and sheep,

Till at last the conversation gets around to Gordon’s Leap:

That famous leap old Gordon made to clear a six-foot hedge,

And land three hundred feet above the Lake on a narrer ledge.

I didn’t question the veracity of this until I was much older.

In 1900, a horseman from New South Wales, Lance Skuthorpe, came to Mount Gambier in order to prove that the leap was possible and put any doubts to rest. (“It was not to show the world that another man could do it,” Skuthorpe wrote to the Coonamble Times in 1933. “It was just to show the people of Mount Gambier that it could be done.”) The accounts of this vary wildly as well. According to some reports, Skuthorpe eventually managed the leap, though only on his third attempt. According to the Gordon cultists, he got onto the ledge but wasn’t able to get back, necessitating the removal of the fence. According to Skuthorpe, clearly given to the occasional rhetorical flourish, “I succeeded on [….] one of the greatest jumpers Australia had ever seen, or, perhaps, the world had ever known.”

This is how the sausage gets made: the peddling of myths by writers and newspapermen, the telling of tales by blokes in bars. People will similarly tell you that Gordon’s ‘From the Wreck’, about the 1859 Admella disaster off Cape Northumberland, was autobiographical, and that Gordon himself made the harrowing ride from the Port MacDonnell coast to the Mount Gambier telegraph station. It isn’t, though, and he didn’t. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend. Until it’s legend, control the narrative.

A couple of months before the leap, Gordon had bought Dingley Dell, doubtless with some of the £7000 legacy he had received in the wake of his mother’s death. A month after the leap, he had his first poem published, in the pages of the Border Watch. (Written in the style of a Scots border ballad, ‘The Feud’ is an acquired taste. I have not acquired it.) At the beginning of 1865, he was asked to stand for the South Australian parliament. Whatever Riddoch later said, while laying the foundation stone of the obelisk, Gordon was widely considered to have performed his duties in a “very perfunctory manner”. (He scheduled his campaign around race meets and spent his days in parliament drawing horses. His entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography suggests that he might have been a better poet had he not been so obsessed with riding, but then it seems he might have been better at a lot of things had that been the case.) But the gig afforded him time to write, and over the two years that he spent in politics his work appeared with ever increasing frequency in the Border Watch, the Australasian, Bell’s Life, and other periodicals. In 1867, his first collection, Sea Spray and Smoke Drift, was published.

But there was something in him, some temperamental weakness, that meant the good times weren’t to last. An ill-advised tilt at squattocracy in Western Australia, along with the financial failure of his poetry, put a significant dent in what was left of his inheritance. At the end of 1867, he moved his family to Victoria, initially settling in Ballarat before later moving to Brighton. In 1868, his daughter died. He was convinced that he was heir to Esslemont, the Gordon family estate in Aberdeenshire, but his attempts to get his hands on it ultimately came to nothing but lawyer’s fees. He had been prone to bouts of melancholy before, but now they were coming thick and fast, exacerbated by various head injuries sustained in riding accidents. At the beginning of 1869, he returned to South Australia to visit Riddoch, staying at the latter’s Yallum Park estate. Riddoch recalled that visit later:

He would mumble away in the saddle with his thoughts far away and it was absolutely impossible to get anything out of him then. I remember when he wrote ‘The Sick Stockrider’ at Yallum, he climbed up a gum-tree near my house, as he often did when he wanted to be quiet, and composed it there. He generally went out after breakfast when he had a poetical fit and evolved his verses there.

The poem begins:

Hold hard, Ned! Lift me down once more, and lay me in the shade.

Old man, you’ve had your work cut out to guide

Both horses, and to hold me in the saddle when I swayed,

All through the hot, slow, sleepy, silent ride.

The dying stockman proceeds to reflect, in a wistful, increasingly meandering fashion, on his life and many exploits. I am reminded—and not only because I know where Gordon’s story is going—of Hemingway’s ‘The Snows of Kilimanjaro’, in which a writer dying of gangrene in Africa reflects on his creative failures. As Riddoch’s biographer, John Rymill, notes, ‘The Sick Stockrider’ becomes “ominously prescient” as it begins to wind down:

Let me slumber in the hollow where the wattle blossoms wave,

With never stone or rail to fence my bed;

Should the sturdy station children pull the bush-flowers on my grave,

I may chance to hear them romping overhead.I don’t suppose I shall though, for I feel like sleeping sound,

That sleep, they say, is doubtful. True; but yet

At least it makes no difference to the dead man underground

What the living men remember or forget.

More than any other, this is the poem on which Gordon’s reputation, at least as an Australian writer, rests. That’s obviously a loaded term, especially in a country where works of art have historically been judged less on their artistic merits than on the extent to which they contribute, or don’t, to the national project or sense of national identity. Both the project and the identity in question have almost always been white, as indeed they were in Gordon’s time. But in Gordon’s time they were also nascent, and it is difficult not to detect in the poem—in the stockman’s display, not of British pluck, but of something more informal and insouciant—the germ of the myths to which we continue to ascribe, or, to put it a little more bluntly, of the lies we continue to tell about ourselves.

It’s also difficult not to detect, well, “something very like the beginnings of a national school of Australian poetry”. Well into the second half of last century, long after Gordon’s star had faded, literary critics could and did argue that “Gordon, particularly with ‘The Sick Stockrider’ […] established the style of the pounding rhythm and the long line which is generally characteristic of the ballads after him” and that the poem “will always mark the moment when the literature of this country began to move in a new and more characteristically Australian direction.” Writing a little more equivocally about how “Australian” the poem is—“The landscape, despite the scattering of place names, is still rather generalised, even English, in its descriptions”—Geoff Page wrote that ‘The Sick Stockrider’ did nonetheless create “the template which later and perhaps more sophisticated balladists like ‘Banjo’ Paterson and Henry Lawson could utilise”. (The other poem Gordon wrote at Yallum, ‘From the Wreck’, undoubtedly served as an influence on Patterson’s much more famous ‘The Man from Snowy River’.)

Page’s suggestion that “Gordon, for all his efforts, is not yet truly assimilated” goes some way towards confirming Sparrow’s thesis, which is that the poet’s cult emerged in part because he “could be presented as an unhappily exiled Englishman rather than an upstart colonial.” Despite the fact that Gordon’s family was Scottish—don’t make that mistake in Glasgow, Jeff—the poet did on occasion refer to himself as an exile, and many Australians at the beginning of last century liked to think of themselves as exiles, too. Sparrow writes:

From a modern perspective Gordon makes an odd choice for a national poet, since he wrote only rarely about the country that embraced him. He set many of his popular verses in England and studded the others with the classical references familiar to an English gentleman. [...] At the ceremony to mark his inclusion in Westminster Abbey, the archbishop of Canterbury described him as “the voice of the national life of one of the young nations of the British race”. He was, in other words, the poet of Australia precisely because of his Englishness.

He goes on to suggest that Gordon fell out of fashion with the advent of WWII, when “[t]he realignment of the Australian state away from British imperialism (and into the orbit of the new American order) meant that Gordon’s unselfconscious Englishness sounded suddenly and irrevocably dated”. This may have been true, but I reckon the fact that he’d been dead for seventy-two years by the time Curtin said that “Australia looks to America” is probably more relevant. Gordon’s “more ambitious poems,” as Leonie Kramer calls them, had always been “heavily imitative of Romantic and Victorian poetry” and was never nearly as popular as his bush verse and “horsey poems”. But bush verse was on its last legs, too. Lawson had been dead since 1922 and Patterson died in 1941. A new generation of poets, such as Kenneth Slessor, considered the forms and preoccupations of bush verse stultifyingly parochial. Is it any surprise that Gordon wasn’t the man for a country that was finally coming around, however trepidatiously, to modernism? Another Mount Gambier boy, Max Harris, would found Angry Penguins and publish the Ern Malley poems before the war was out.

For his part, Gordon was pleased with ‘The Sick Stockrider’ and excited when it was published in Colonial Monthly and the Australasian. He wrote to Riddoch:

[D]id you like those verses of mine, ‘The Stockrider’? [...] [T]hey made quite a stir here & were copied into The Australasian & spoken of with praise [though] I don’t think much of them myself.

Perhaps that note of self-deprecation was false modesty or perhaps it was a warning sign. Either way, the honeymoon didn’t last. On 23 June 1870, Bush Ballads and Galloping Rhymes was published, with ‘The Sick Stockman’ among the collected poems. At dawn the next morning, Gordon walked down to the beach and shot himself with his rifle. The irony of ‘Ye Wearie Wayfarer’, which includes the most famous lines Gordon ever wrote, is palpable:

Life is mostly froth and bubble,

Two things stand like stone,

Kindness in another’s trouble,

Courage in your own.

Dingley Dell has been closed to the public since the previous caretakers, Allan and Jenny Childs, gave up the lease in 2020. They had run the place—giving tours, tending the gardens, assisting visiting researchers—for twenty-three years. South Australia’s Department for Environment and Water continues to maintain the surrounding scrubland but has been unable to secure a replacement caretaker and is in the process of finalising the management plan it has been attempting to finalise for years. Successive proposals, including a controversial plan to turn the site into a glampground, have thus far come to nothing.

I had been told that I should ride out to the cottage and at least take a bit of a look through the windows. But when I got there the windows were blacked out and the gardens were weedy and overgrown with lavender cotton and seaside daisy. I briefly considered breaking in but eventually thought better of it.

A little sleuthing put me in touch Lorraine Day of the Adam Lindsay Gordon Commemorative Committee. Day put me in touch with the Limestone Coast Manager for National Parks and Wildlife, Nick McIntyre, who in turn arranged with a local, who had the keys, to let me into the building.

I went over again on Friday afternoon with my mother and six-year-old nephew. It was my last day in Port MacDonnell. Our connection had already opened the house and left us to wander around on our own. It smelled exactly the way you would expect it smell after being shuttered, but for the occasional open day, for nearly half a decade.

For whatever romantic reasons of my own, I had expected something a little smaller, a little more utilitarian. In fact, it’s spacious as cottages go, with four rooms leading off from a central hallway decorated with equestrian prints and presided over by a glowering portrait of Queen Victoria. I unroped each of the rooms in turn. The first on the left was a sitting room, containing portraits of Gordon and his wife, an upright piano, a violin, and an ancient squeezebox. An ashtray designed to look like a tortoise, apparently from 1853, sat on the mantle. The bedroom is across the hall. The next room down on the right is the study—or rather has been fashioned as a study—complete with a seagull feather in an empty inkwell and a library that includes three secondhand copies of Edith Humphris and Douglas Sladen’s 1912 biography of the poet and several tattered editions of his poems.

Dingley Dell was built in 1862, two years before Gordon bought it. (It was only the seventh building anywhere to be built with Mount Gambier stone.) One of its later caretakers, Charles Elliott Perryman, described the cottage as follows:

It was a plain double fronted little cottage very new and prim among the leafy wilderness of bush clad hills. A bush road led by the place up and away over the hills to the West where it joined the main road to Gambierton.

Wire fences were non-existent and [there was] a straggling log fence over which pink and white roses grew and thrived, together with the pale blue periwinkle. The log fence has passed away only the periwinkle remains on the slope of the hill beside the old house where a poet slept and dreamed.

In 1873, three years after Gordon died, his wife, Margaret, gave the cottage to the local council. Forty-nine years later, in 1922, the South Australian government bought it at the urging of the Dingley Dell Restoration Committee. It was, at the time, the oldest historical residence in the government’s possession. Perryman described what had happened to it in the intervening years:

Many tenants passed through its homely doors in the years that followed [Gordon’s death] until in the beginning of this century it was given over to chance callers, tramps, and visitors who wrote their names in many mediums upon its plastered walls.

Sheep were shorn in its rooms, and the wild bees built their hive in the corner of the wide chimney place in the kitchen, where at one time Margaret Gordon prepared her good man’s meals.

In 1980, the cottage became the first building to be listed on the South Australian Heritage Register. As a tourist attraction, its golden age seems to have been that of the Childs’ stewardship. Allan Child, in particular, despite knowing little about Gordon before taking the lease, became something of a Gordon tragic, and set about filling the cottage with memorabilia. He also took to answering the phone in character as Gordon. He died last year.

The second room on the left is what remains of his museum. While many of the more important artefacts are now in storage somewhere in Mount Gambier, the room is still very busy. Scenes from ‘How We Beat the Favourite’ line the walls in dusty picture frames, portraits jostle for space alongside newspaper clippings and sketches of Gordon’s homes. A model of the Admella sits on a glass case containing a trooper’s saddle—“similar to that used by Gordon,” we’re told—as well as Margaret’s sidesaddle.

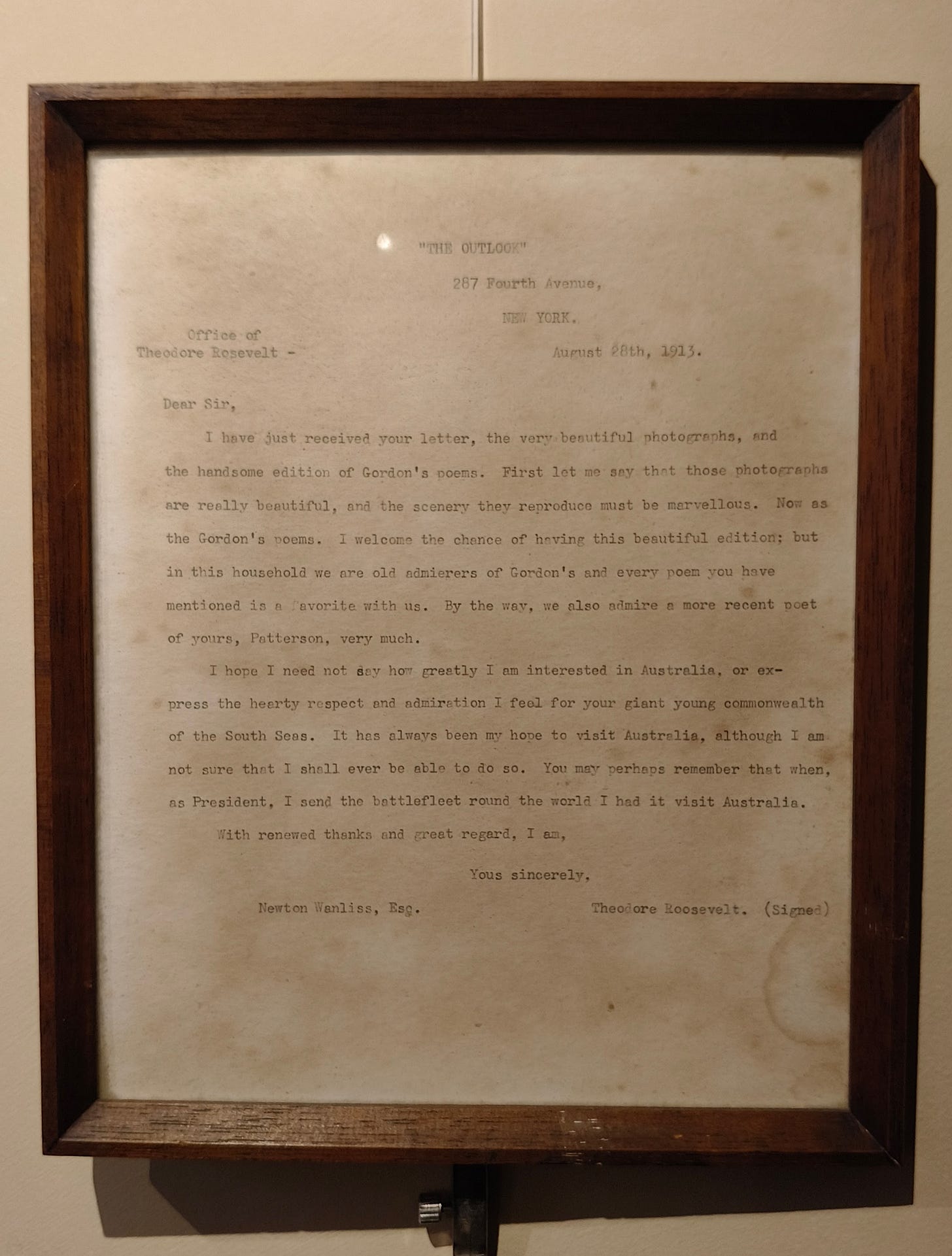

But what caught my eye were the two framed letters, each in facsimile, to the right of the doorway. The first was written in the offices of The Outlook, a magazine headquartered on Fourth Avenue in New York City, by former US president Theodore Roosevelt:

Teddy always was the horsey type.

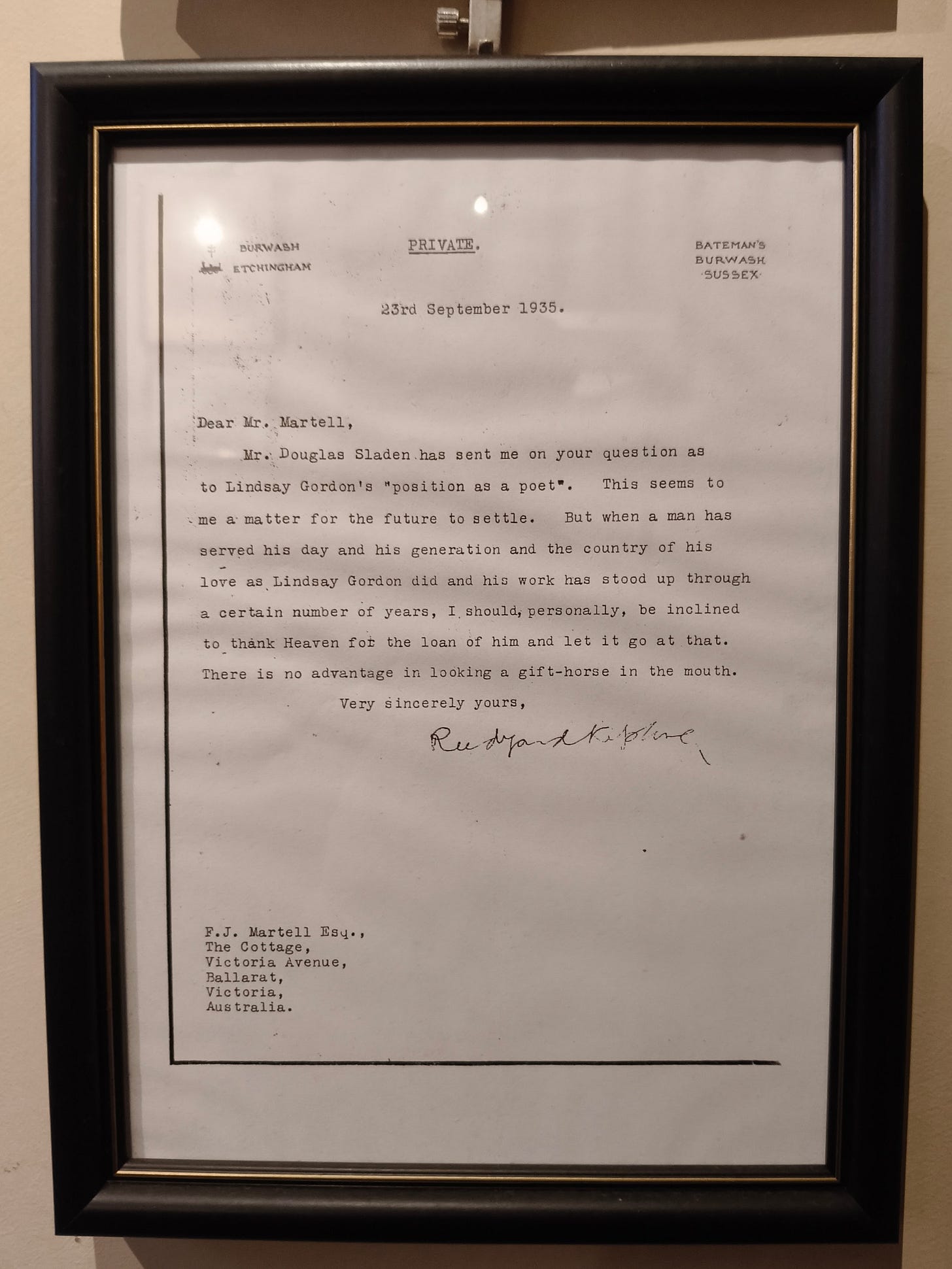

The second letter is even more striking. It is addressed to F. J. Martell, who was instrumental in having Gordon’s Ballarat cottage moved to the town’s botanical gardens:

This note from the fabled Poet of Empire would seem to bring Gordon’s story full circle: from Berbice and Bengal to the Blue Lake and Brighton to Bateman’s in Burwash, East Sussex. It would seem, too, to give added weight to Sparrow’s argument about Gordon’s posthumous success being tied up in fantasies of Empire and exile. (Of course, in the end, Sparrow’s article isn’t really about the Gordon cult at all. Like everything else he’s ever written, it’s actually about how the left might rise again and strike a decisive blow against the right. He’s always seeing some new opening or opportunity. In this case, it’s the emergence of “a renewed literary infrastructure” that “seems much less likely to take shape as a nationalist venture than as a counter-hegemonic project, drawing its energy from movements for social change,” even though that doesn’t seem very likely, either.)

I maintain that aesthetic irrelevance has more to do with Gordon’s fading from memory than the British Empire’s fading from world affairs. I don’t think geopolitics killed the cult. For one thing, as I discovered while writing this piece, the cult never really died. The same people who were once powerful enough to get Gordon into Westminster Abbey and his poems in front of presidents and Nobel Prize winners are now content to make some calls and track down the keys to an old museum. The cult has become a literal cottage industry.

Don’t get me wrong, though. It’s still kind of weird. Sparrow writes of a tree stump in Brighton that bears a plaque commemorating the fact that Gordon once tethered his horse to it. In a room off the kitchen at the back Dingley Dell, which is used for storing old visitor pamphlets, I discovered a bulging folder of ephemera that included a letter from Queen Elizabeth II’s Deputy Private Secretary, politely declining an invitation to Her Majesty to become a patron of the Adam Lindsay Gordon Commemorative Committee, and an entry form for the Esperanto Federation of Victoria’s Adam Lindsay Gordon Esperanto Poetry Competition. Rather more offputtingly, there is a lock of hair belonging to Gordon’s daughter, Annie, on the wall of the museum, as though it were a kind of religious relic. Annie was ten months old when she died. I don’t think her hair needs to be on display.

This kind of thing is the residue of romanticism, a cringeworthy form of genius- or hero-worship that we don’t see much today outside the secret diaries of adolescents. At least as much as Australia’s changing self-image, though still less than its evolving aesthetic standards, it’s the fading away of this sensibility—the realisation that Werther is not a model to be emulated but rather a pretty troubled young man—that I think explains Gordon’s gradual eclipse. By the time we got to the end of WWI, and shell-shocked soldiers like Septimus Smith started returning home from the front, the conception of the noble, philosophical suicide, undertaken by those, usually men, of refined sensibility, had lost a lot of its currency and appeal. No one older than about seventeen talks of Woolf or Plath or Hemingway as being anything other than deeply unwell. It is only in pockets like Dingley Dell that a tendency to swoon lives on.

My main problem with this is not that it’s sophomoric, but rather that it tends to flatten the object of its affections. In the shrine-like atmosphere of Dingley Dell, Gordon has been turned into a secular saint, where in fact he remained the same wild child he always had been. He was a gadfly and a spendthrift and preferred horses to poetry. He shot himself, not because he felt the world too keenly, but because he’d spent all his money. The Gordon of the cultists is an Orthodox icon. The Gordon who got kicked out of school, risked his life for a laugh, played truant from parliament, and wrote his best work in trees sounds like someone you could actually hang out with.

As we drove to Mount Gambier’s coach station on Saturday morning, people walked and jogged around the Blue Lake without so much as glancing at the obelisk. Like a family heirloom, it has been passed down through the generations to the point that no one can remember where it came from anymore, or when, or what it symbolises. Dingley Dell has been shuttered again and will likely remain locked, unvisited, until May, when there is to be another open day. “There is a queer local apathy to Gordon in the district,” wrote Perryman. “He is mostly regarded as a peculiar, taciturn fellow who rode wildly across country, and over fences, [and] that he wrote poetry that is largely ignored.” It seems to me that little has changed.

I am not especially surprised that Mount Gambier rarely talks about Gordon, though. It rarely talks about Robert Helpmann, either. We’re a regional community and our heroes are not artists. It nevertheless remains true that it was here that Scots border balladry became Australian bush verse. That’s not nothing. Whatever you think about such poetry as poetry, let alone about its colonial history or post-Federation politics, it remains an integral part of our literary story, and there’s no getting around the fact that Adam Lindsay Gordon was its originator. I’m personally rather tickled to think that it was born only fifteen minutes from my parent’s house.

Glad the family visit not only went well but produced this wonderful bit of writing.

Think the saccharine romanticism is a bit missed on my part. Bush poetry and romantic paintings always remind me of being at my grandparents (seeing the prints McCubbin on the walls, being given boys own adventure books, etc). After the world wars too many broken people to widely enjoy the occasional tragedy, but was definitely a guilty pleasure in the Lovett house...

An engrossing myth archaeology & social historiography & critical analysis & horseman rebuttals & local mapping, plus a parallel series of Sparrow skirmishes. Hugely enjoyable.